A four-tiered model for crowdsourcing fungal biodiversity citizen science

Fungi may represent half of all multicellular life on Planet Earth1 and are critically important to both humans and ecosystems, but they are poorly understood by scientists compared with plants and animals. We have nowhere near enough professional mycologists to document all of North America’s fungi. Although protocols are well-developed for collecting and documenting fungi, there simply are not enough trained professionals to get the job done. Funding and time to survey are just too limited.

There are, however, literally millions of people who find fungi fascinating. The energy and intellect of interested amateurs can be extremely impressive. Unfortunately, not everyone who is interested in fungi has the skill sets or discipline to produce data of high quality.

Our challenge, then, is how to tap into the power of interested people and have outcomes that move science forward. I propose here a four-tiered system that engages people initially in fairly simple scientific tasks, while encouraging and enabling those who want to do more rigorous and sophisticated science. At each stage amateurs can make valuable contributions to science, provided attention is paid to continually improving data quality and that data are posted on public platforms.

Fungal Diversity Survey's (FUNDIS) original idea was to require all participants to accomplish all three activities that professional mycologists undertake to study fungal taxonomy: extensive documentation; sequencing DNA, and preserving dried specimens in curated fungaria. With two years of operation under our belt, however, it’s apparent that this model is overwhelming for aspiring citizen scientists without training, and will never scale up. Moreover, it represents a limited view of what constitutes legitimate science in the era of crowdsourcing.

Imagine a pyramid with a large base of citizen scientists doing basic field photo-documentation of fungi. A portion of those will want to “move up” to do more scientifically robust DNA sequencing of photo-documented specimens. And a subset of those will choose to do the “whole shebang”: make detailed field and lab descriptions, sequence specimens, and preserve dried vouchers in curated fungaria. Finally, the most motivated “super users” will engage in extracting DNA in home or school do-it-yourself labs; teach others how to analyze DNA sequences; and perhaps even describe new species.

Level 1. Observe: Document fungi in the field with geo-referenced color photos and post observations on public, databased platforms.

Level 2. Sequence DNA: Level 1 + Submit tissue for DNA sequencing, interpret results.

Level 3. Voucher: Levels 1&2 + Preserve well-documented, dried specimens in curated fungaria.

Level 4. Super-user: Learn DNA technology, teach others how to analyze DNA results & make phylogenies; describe new species.

Level 1. Observe: Document fungi in the field and post observations on public, databased platforms.

At the simplest level, photo-documenting fungi in the field with timestamp and GPS, and uploading those observations to the Internet, can, with several provisos, add valuable knowledge to understanding the distribution of fungi as well as changes over time. Such information is especially valuable in a time of changing climate. Scientific value depends on at least three conditions.

First, there must be a commitment to data quality and to continual improvement of photo technique and recording critical information such as habitat, substrate, odor, taste and staining (“metadata”). Clearly, more data means more scientific value, increasing step-wise with more metadata,. Beyond simply posting an image to Mushroom Observer or iNaturalist, value increases as the observation includes:

geo-coordinates and time stamp

ID confirmation by other users ("Research Grade" on iNat, "Community Vote" on MO)

measurement data (could be a ruler in photograph)

clear photos, more than one, of different parts

multiple growth stages

habitat/substrate data

other field metadata (odor, taste, staining, chemical test, etc.)

lab metadata (spore color, macro photos, etc.)

images from microscopy

Any image with geo-location and timestamp data has some scientific value. If you want to increase the scientific value of your observation, provide more metadata. Many data quality problems could be solved with active participation of clubs or online experts training project participants to take better photographs and to collect more detailed information.

Credit: Michelle C. Torres-Grant

Second, observations must be uploaded to a searchable (“databased”) platform. FunDiS projects use iNaturalist or Mushroom Observer. Sites like Facebook and Instagram are important for learning and sharing, but they do not contribute directly to scientific goals. Many users, myself included, log detailed observations on iNaturalist or Mushroom Observer and then post links in taxonomically specialized Facebook groups to get feedback from expert users.

The third determinant of scientific utility of crowdsourced field documentation is scale. A small number of scattered observations seldom reveals robust patterns. But the essence of crowdsourcing is the collection of massive amounts of data across space and time that would be impossible otherwise. Consider what the crowdsourced app eBird has achieved for the scientific study of bird populations. eBird posts 100 million observations per year and, based on those data, scientists have published more than 300 peer-reviewed papers. iNaturalist provides an easy-to-use field app, but with a total of some 800,000 fungal observations (Mushroom Observer has perhaps half as many) there need to be many more observations in more locations before the data will be valuable for ecological analysis.

Another issue is identification curation (putting valid names on observations), which is both useful for verifying identifications and for quality control. eBird addresses identification curation with an expert reviewer network of some 1,300 volunteers who monitor observations, in addition to the use of Artificial Intelligence (which iNaturalist also uses). Mushroom Observer and iNaturalist do not have formal expert reviewer networks built in, but such expert review can and sometimes does arise organically within projects, clubs or regions.

On the other hand, while birders have some inherent advantages, monitoring fungi has a big advantage for scientific value: mushroomers can take close-up color photographs, collect specimens and even sequence DNA. By comparison most eBird observations are merely hearsay records of what was seen or heard.

The pool of potential citizen scientists fascinated by fungi is significant. The 10,000 members of 80 clubs affiliated with the North American Mycological Association is just the tip of the iceberg. A single Facebook mushroom group has 170,000 members (mostly young), and there are many Facebook and Instagram groups devoted to fungi. If 100,000 or 1 million citizen scientists learned to take and post scientifically useful geo-tagged field photos, not only would we be building an important body of ecological and taxonomic data, we would also be creating a pool of individuals who will want to learn more about science and move up to the next level.

Level 2. Identify: Submit tissue for DNA sequencing; interpret results.

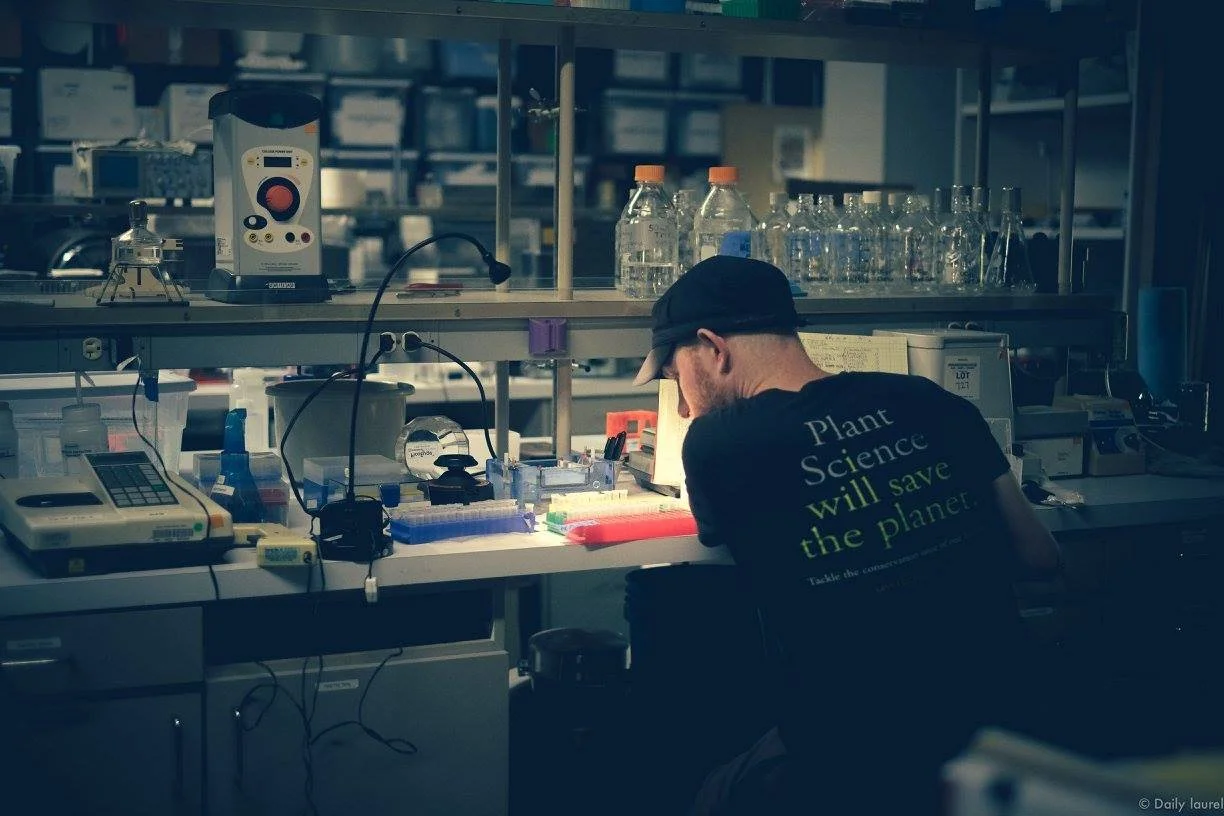

A second level of legitimate citizen science is sequencing a length of DNA from specimens that have been photographed and documented in the field. In one sense, an organism’s DNA is just another descriptive character, but it is an extraordinarily useful character because DNA ultimately determines most of the other characters we can measure with our eyes, a camera or a microscope; and it can tell us about evolutionary relationships. For most citizen scientists, sampling DNA means taking a piece of dry tissue from a specimen, sending it to a lab for sequencing, interpreting the results, and ensuring that sequences are eventually posted to GenBank. This level of citizen science addresses a key motivating factor for amateur participants: the desire to put names on locally collected specimens.

Can sequences without vouchers add value to science? Professional mycologists would never sequence a specimen that was not preserved in a curated fungarium, and that’s clearly ideal. But amateurs have more limited access to space in curated fungaria (see Level 3). Posting sequences of specimens to GenBank adds measurable scientific value if the sequences are linked to color photos and other metadata. And getting many more photo-documented, geo-referenced sequences will improve the usefulness of GenBank (which is somewhat limited now) for making species identifications. Such sequences are also useful for building phylogenetic trees, thus drawing attention to where future collecting efforts might profitably be directed. Finally, new “NextGen” barcoding technology may soon allow sequencing many more specimens at significantly lower cost per specimen, exceeding the current storage capacity of most fungaria.

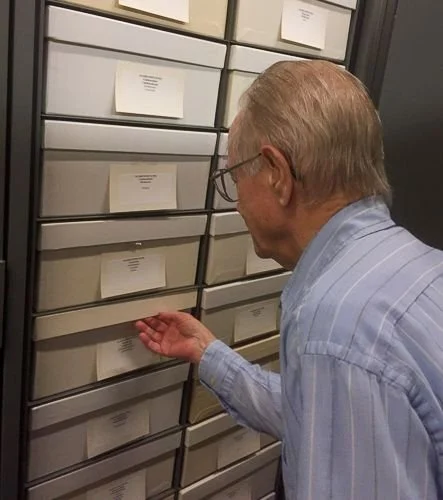

Level 3. Voucher: Preserve well-documented, dried specimens that have been sequenced.

Saving dried vouchers of sequenced specimens is ideal; it’s what FunDiS recommends wherever practical. Records of specimens in curated fungaria are aggregated on a platform called MyCoPortal, which is where professional mycologists currently go to find specimens they want to study. Preserved specimens allow user identifications to be checked by specialists and, more importantly, scientists examining specimens in the future will undoubtedly have more powerful tools to re-sequence DNA than are currently available.

Credit: Bill Sheehan/Dick Hanlin UGA Fungarium

There are practical limitations to putting specimens in fungaria. Curated fungaria have costs for both space and staff and they do not want to accept specimens of poor data quality nor examples of the most common fungal species (Do we really need another Trametes versicolor?). FunDiS needs to develop procedures to flag and ensure that the most valuable specimens get vouchered in curated fungaria, at least for those FunDiS participants who are not advanced amateurs who know when something is taxonomically interesting. Such triage procedures could be based on expert review of images and sequences posted on the Internet. For the citizen scientist this will require storage of dried specimens at home or in a club herbarium until their value is ascertained by experts.

The bottom line is that preserving well documented specimens provides the most robust scientific data for documenting fungal biodiversity; but Level 1 and 2 activities, when done well and at scale, also contribute to scientific knowledge while initiating a broad range of people into the scientific method.

Level 4. Super-user: Teach others how to analyze DNA results; sequence DNA in home/school labs; describe new species.

Every citizen science project has an elite cadre of “super users” who want to know and do more, and who function much like unpaid professionals. The mushroom world is no different. Already some FunDiS project leaders have mastered the intricacies of analyzing DNA sequence results, cleaning up trace files, and making phylogenetic trees. They have also indicated a willingness to teach others. Some have even worked with professional mycologists to describe new species.

Still others are keen to try their hand at DNA extraction and amplification at home using simple equipment purchased on eBay. This kind of hands-on experimentation is of particular interest to young people, like some in the Radical Mycology network, who are motivated to go beyond identifying fungi to finding practical applications.

*******

What would it take to grow the amateur mushrooming community from the present perhaps 100 Level 3 and 4 advanced amateurs and super users in North America to 1,000? If the answer is 10,000 Level 2 participants self-recruited from 100,000 Level 1 participants, how can we achieve that using distributed technology and crowdsourcing?

If our conception of fungal citizen science is limited to what professional mycologists have done historically (Level 3) we will never scale up to put a dent in documenting the North American funga. Consider the legendary professional mycologist Rolf Singer, who was active in the mid-1900s. He did not have access to tens of thousands of volunteers with cameras that take high-resolution color photographs and record geographic location. Nor did he have access to the Internet, let alone to DNA sequences! We can accomplish so much more.

Our challenge is how to marshal the great passion for mushrooms evident in the public to do legitimate science that contributes basic knowledge needed to understand the roles of fungi in ecosystems and in the health of the people and other organisms who inhabit Planet Earth.