FunDiS West Coast Rare Fungi Challenge

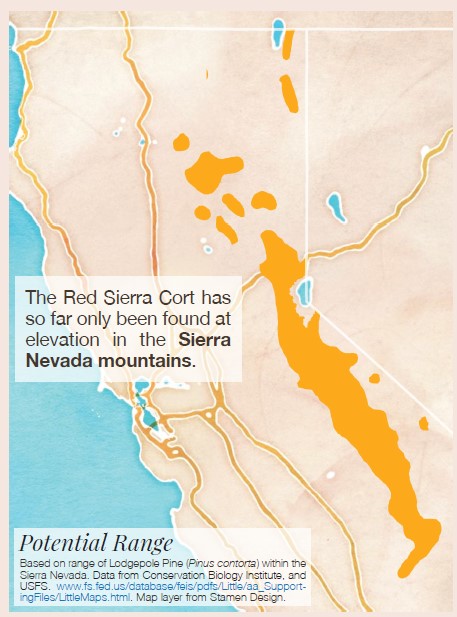

The Red Sierra Cort relies on lodgepole pines for its sugars (carbohydrates), and with the demise of lodgepole pine, the mushroom is also threatened.

Description

What else could it be?

A number of other red/reddish Cortinarii can be found in western North America, all differing rather subtly from each other, but each with its own habitat and host preferences.

C. rufosanguineus, C. neosanguineus, C. smithii, and C. phoeniceus all have red caps. There are also a couple of red-capped Tubaria species that look similar, but don’t grow with lodgepole pines.

When you find any of these red-capped species, look around and note the tree species above the mushrooms. And if you have permission to do so, collect and dry the high-elevation red-capped ones for follow-up research on this group.

![]() Never eat wild mushrooms without a confident identification!

Never eat wild mushrooms without a confident identification!

Contact Poison Control if you think you have eaten a poisonous mushroom: 1-800-222-1222

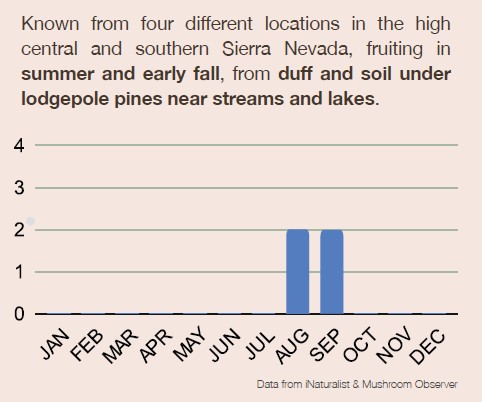

When & Where?

Habitat

More information

http://iucn.ekoo.se/iucn/species_view/800335/

iNaturalist (1 obs.):

iNaturalist.org/taxa/559916-Cortinarius-sierraensis

What to do if you find it:

Make an observation

The first thing to do is to record your observation. We prefer to use the iNaturalist app for that (visit www.iNaturalist.org to learn more), but you could also upload your observation to Mushroom Observer (visit www.MushroomObserver.org). The QR code to the right will take you to the Fungal Diversity Survey (FunDiS for short) website to explain how to contribute to the project.

The first thing to do is to record your observation. We prefer to use the iNaturalist app for that (visit www.iNaturalist.org to learn more), but you could also upload your observation to Mushroom Observer (visit www.MushroomObserver.org). The QR code to the right will take you to the Fungal Diversity Survey (FunDiS for short) website to explain how to contribute to the project.The best thing you can do is take lots of photographs and notes. Typically, smartphones will automatically georeference any photos taken, but it is good practice to note your exact location, preferably with GPS coordinates, and what trees or other habitat features are nearby. For example, was the mushroom growing from duff and humus, or from bare soil? Did it have a particular smell?

Collect a specimen

If you are in an area where it is allowed and have any necessary permits, we strongly urge you to create a vouchered collection. This means a dried specimen for deposit in a herbarium, where researchers can access it for things like DNA sequencing. If you don’t know how to do this, please see:

fundis.org/sequence/sequence/dry-your-specimens

In California, collecting mushrooms is usually allowed in National Forests with a permit. Permits can be obtained at the headquarters of the National Forest you're visiting, and are usually inexpensive or free. However, restrictions vary among the individual National Forests, so make sure to find out the specifics when picking up your permit. State and County Parks generally do not allow mushroom picking, but regulations vary, so make sure to check your destination before you go out. In Arizona and other Southwestern states, most Forest Service and BLM lands allow collecting for personal use without a permit, but again, regulations vary, so check ahead of time.

Don’t forget to look for other mushrooms and fungi while you’re there! Like other Rare Fungi, part of why this mushroom is rare is because it grows in a place that mushroom pickers don’t generally go: wet areas in the mountains. Since you’ve already got iNaturalist open, why not record your other finds?

Most mushrooms are like fruit: picking an apple from an apple tree doesn’t hurt the tree. In the same way, harvesting mushrooms does not generally hurt the mycelium of the fungus. We do still recommend leaving some mushrooms behind, and not picking perennial mushrooms, like brackets and conks.

Who to contact

If you think you’ve found this mushroom, and you’re not sure about any of the above, such as how to report the find, whether you can collect it, or what to do with it once you have collected it, please contact us!